In 1948, French film critic Alexandre Astruc wrote an article titled: “The Birth of a New Avant-garde: La Camera-stylo”, whichchallenged the then current model of cinema, after being dissatisfied with the quality of Hollywood film that saturated postwar France. Astruc emphasised the director’s ability to translate their obsessions and creative ideas to reach the great achievements that existed within other art forms, using the literary author’s pen as a metaphor to grasp cinema. Astruc’s idea would be followed up in Cahiers du Cinéma, an influential French film magazine co-founded in 1951. The magazine included many influential French New Wave directors amongst its writers, including Francois Truffaut, who expanded upon Astruc’s writing and produced his own works “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema” (1954), and “Authors’ Policy” (1955), which proposed that the director is the true author of a film – the auteur. In 1962, film theorist Andrew Sarris reinterpreted Truffaut’s essays for Anglo-American filmmakers and coined the term “auteur theory”, which has become the “best-known theory of cinema” (Crofts 1998:310). Alfred Hitchcock is a director that is integral to both the discourse surrounding auteur and the history of Hollywood, being held in high esteem despite working in the studio system. This essay focuses upon auteur theory, and critically evaluates the notion of the director being the true author of the film, by reflecting upon Alfred Hitchcock, his work, and his relationship to Hollywood.

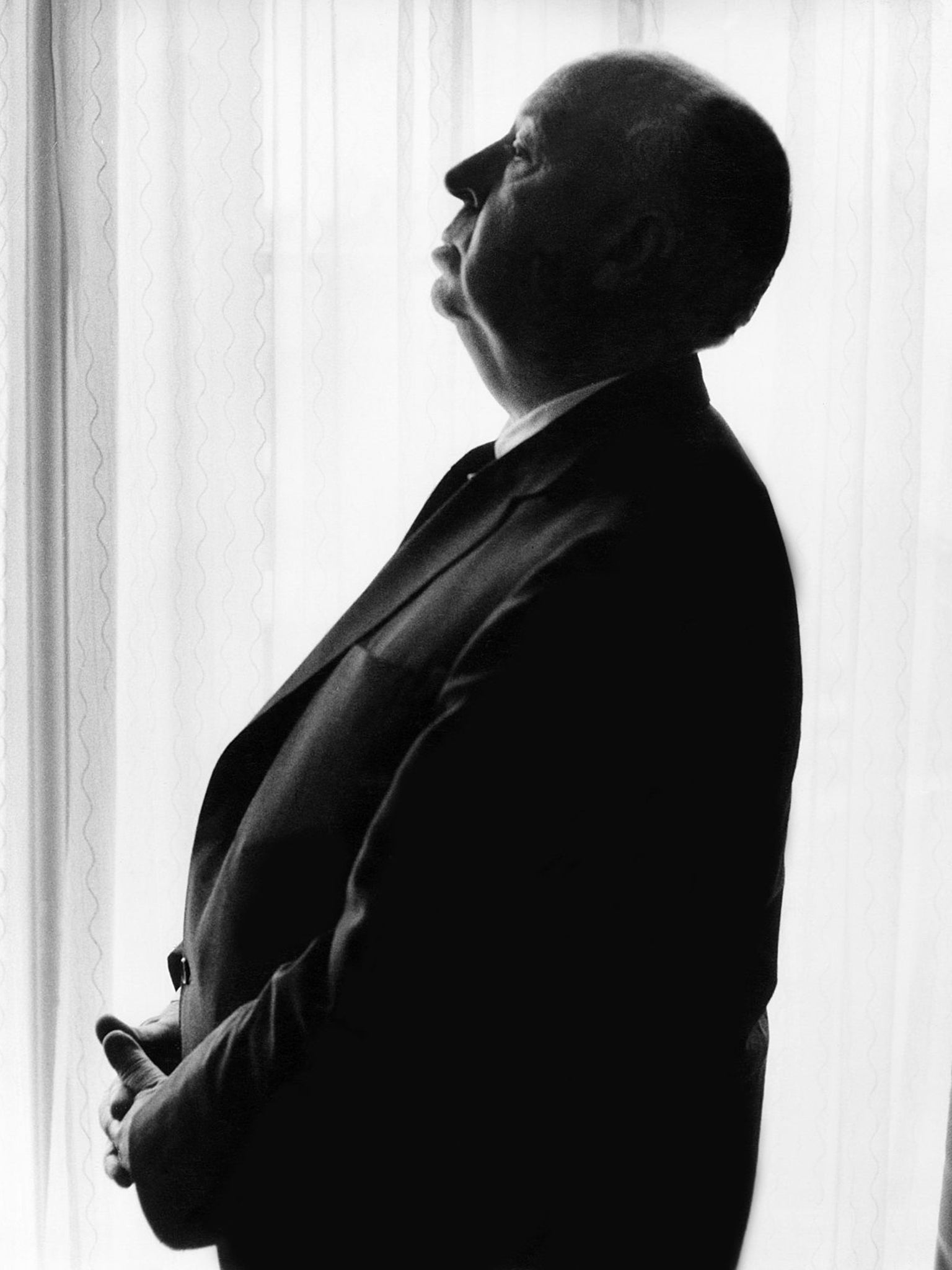

Born in England, Alfred Hitchcock was highly influential, directing the first British sound feature film Blackmail (1929), before moving to America to produce films in Hollywood such as Rope (1948), and Under Capricorn (1949). Films directed by Hitchcock in the late 1940s flooded France, with reception from fellow cinephiles being mixed. Astruc viewed the films positively and used Hitchcock as an example of somebody who had “proved himself capable of writing cinema with a camera, with style and internal unity” (Vest 2011:358). In Astruc’s view, Hitchcock had mastered La Camera-stylo and was a master storyteller, thematically linking his films with metaphysics, and defending Hitchcock’s use of an opening flashback within Stage Fright (1950). The significance of directors began to grow, and in 1962 Sarris adapted the auteur theory from French film criticism, a broad term that has been accepted into film theory and criticism.

Despite auteur theory successfully assimilating into critical discussion, it has been heavily scrutinized. Many commentators have noted it fails to theorise or justify its critical tools, and “arbitrarily attributed significance to the work of some directors over others” (Crofts 1998:311). The lack of a framework to allow for critical evaluation has led the theory to become individualistic by nature. It lacks solid empirical grounding to become a clearly defined concept, and hails Hitchcock as an auteur despite other directors within the system not being labelled as such. It disregards Hitchcock’s relationship with the studio system, and the collaborative effort from designers, cameramen, composers, and writers, some of whom “ultimately began to demand appreciation for their contributions to Hitchcock’s masterpieces” (Coffin 2017:10). Other elements such as actors and stars are part of this film system, and their efforts in Hitchcock films are overly simplified into terms and character types such as “Hitchcockian” and “Hitchcock Blonde”, with the actors themselves rarely receiving any credit for their performance.

While the terms Hitchcockian and Hitchcock Blonde are reductive analysis of the collective effort, when solely analysing Hitchcock, such terms are useful, revealing recurring motifs throughout his work such as Catholicism, dreams, masculinity, and voyeurism, which are all portrayed within his self-reflexive film Vertigo (1958). Furthering this self-reflexivity is the recurring motif of obsession. Hitchcock actively disliked actresses with overt sex appeal and favoured “the sophisticated blonde who becomes a whore in the bedroom” (Truffaut 1968:189). This sexual fixation reared its head into his work, starting with Grace Kelly in Dial M for Murder (1954) and carried on with Kim Novak in Vertigo and Tippi Hedren in The Birds (1963). Hitchcock manages to translate his sexual obsession onto screen, which reaches a peak in Vertigo, as main character Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) becomes obsessed with a dead woman, and forces his girlfriend to dress like her, even wearing a blonde wig.

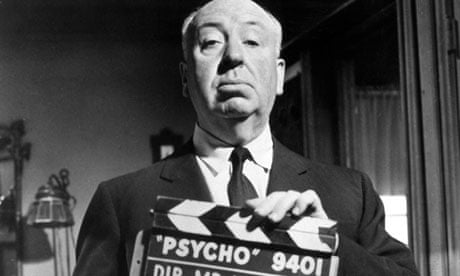

Hitchcock’s narratives are filled with various recurring motifs, but a particular narrative trope, which he adopted from Angus MacPhail, is the MacGuffin – a recurring plot device throughout his films. MacGuffin is a term used to describe a desired object or event that serves as the main motivator for the characters, although it may be insignificant by end of the narrative. Hitchcock frequently used this device, beginning with Blackmail and carried on throughout his career with films such as Rope, and North by Northwest (1959). Psychoanalytical readings from film scholars claim that “when it is an object, it frequently hints at a sexual meaning” (Walker 2005:39), which can be examined in Psycho (1960). Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals $40,000 (the MacGuffin) to run off with her lover, after its hinted that the two had sex during the opening sequence. Marion is ultimately killed, which can be analysed as punishment for the theft, but also for being an overtly sexual, something Hitchcock disliked.

Auteur theory provides a holistic approach towards film analysis, encouraging analysis of entire works instead of individual films. It emphasises consistency of style and themes, allowing for deeper examination of a director’s artistic expression and their motifs that appear throughout their work. Hitchcock’s films have a consistent thematic preoccupation and distinctive style, making him align with the core principles of auteurism. While he could be viewed as the true author of his films due to the personal nature of each of them, auteur theory does not offer a solid framework for examination, meaning that the idea of him being an auteur is purely subjective. The theory neglects the collaborative nature of filmmaking, the various members of crew that helped define terms like Hitchcockian, and Hitchcock’s status as an auteur with his dignified style.

Bibliography

COFFIN, L.L. (2017) Hitchcock’s stars Alfred Hitchcock and The Hollywood Studio

System. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield.

CROFTS, S. (1998) The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Oxon:Oxford University Press.

TRUFFAUT, F. (1968) Hitchcock. London: Martin Secker & Warburg.

VEST, M. (2011) ‘French Hitchcock, 1945-55’ In: LEITCH, T.M. and POAGUE, L.A. (2014) A companion to Alfred Hitchcock. Chichester, West Sussex. Wiley-Blackwell.

WALKER, M. (2005) Hitchcock’s Motifs. Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Filmography

Birds, The. 1963. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Alfred Hitchcock Productions.

Blackmail. 1929. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. UK: British International Pictures.

Dial M for Murder. 1954. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Warner Bros.

North by Northwest. 1959. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Rope. 1948. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Transatlantic Pictures.

Stage Fright. 1950. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Warner Bros.

Psycho. 1960. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Shamley Productions.

Under Capricorn. 1949. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. UK: Transatlantic Pictures.

Vertigo. 1958. ALFRED HITCHCOCK dir. USA: Alfred Hitchcock Productions.

Leave a comment