For this essay, I was restricted to 1000 words and had to describe British kitchen sink dramas that developed post World War 2. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was used as a contextual analysis, in which we had to discuss the first fifteen minutes of the film. It received a 2:1.

For almost all the 1950’s, British cinema was dominated by the social problems genre. Most of the films conformed to conventional filmmaking standards of the mainstream, making them tightly focused and ensuring closure to the viewer. This style of conformity filmmaking is regarded as the first ‘strand’ of British realism cinema. The second ‘strand’ of realism cinema can be traced back to the ‘free cinema’ movement in 1956.

Free cinema is a term associated with six short documentaries shown at the National Film Theatre between February 1956 and March 1959. ‘Free cinema’ is a reference to how films were made free from box office expectations and propaganda. This movement gave birth to the ‘British New Wave’, a more experimental style of filmmaking. Taking inspiration from the ‘French New Wave’ as well as film noir, this second strand of British filmmaking is recognised to have begun in 1959 and was a stark contrast from the first.

The movement began with Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top (1959) and was expanded upon by various directors within different stories such as: Look Back in Anger (1959), A Taste of Honey (1961) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). These films focused on the working class, allowing taboo subjects such as: adultery, abortion, alcoholism, homelessness, and sexuality to be displayed. The British New Wave is a part of a cultural movement known as ‘kitchen sink realism’. Chansky (2015), defines this movement as “a new kind of Post-World War II realism, ‘kitchen sink’ was also known as ‘angry theatre’ or ‘committed theatre’… It provided a look at domestic life in a way that appealed to traditional theatregoers.” Coronation Street (1960) and Eastenders (1985) are modern day examples of ongoing kitchen sink dramas.

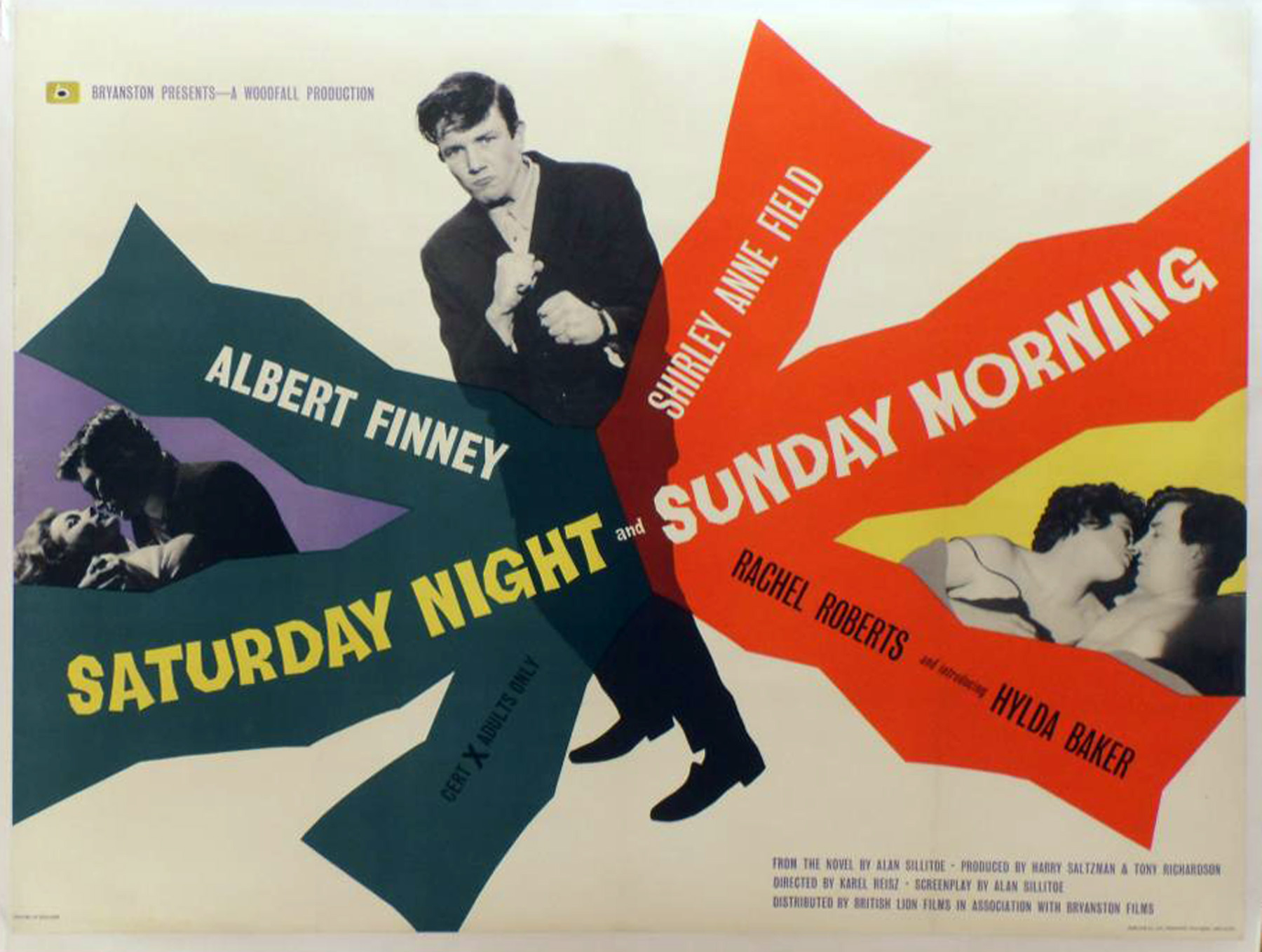

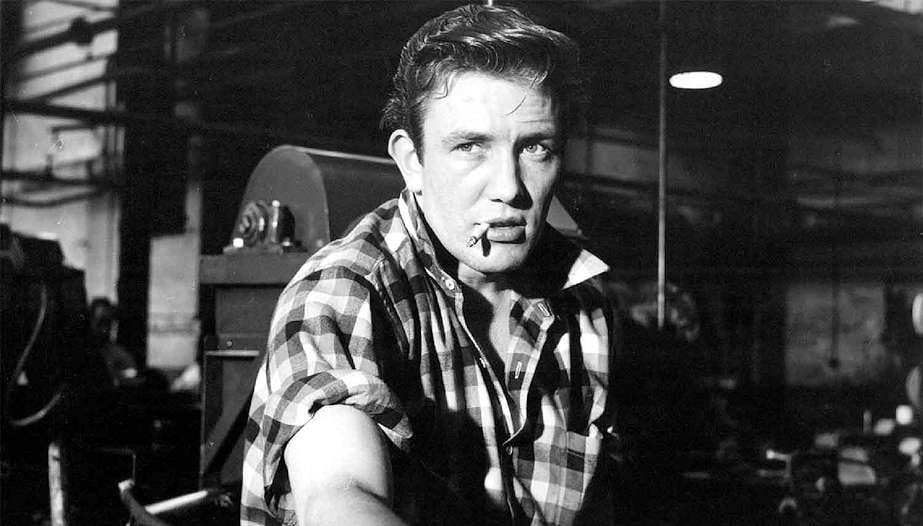

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) is perhaps the best example of a kitchen sink drama within British cinema. The film touches upon illegal abortions, adultery, alcoholism, vandalism as well as featuring a rebellious, young angry man in Arthur. As we see in the opening sequence, the repetitive nature of manual labour leaves little room for self-expression. Arthur makes a point using voice-over, that the older workers around him have been ground down in a way he wants to avoid. A high-angle outdoor shot in the next sequence shows men and women leaving the factory and flooding the frame of the shot. The journey of leaving work to home, as well as the one they’d have to make in the morning, home to work, emphasises the repetitious and hardworking lifestyle that governs their lives. While Arthur states his rebellious nature by a voice-over, we soon find out he enjoys money too much to stand against his oppressive elders.

It’s made clear to us Arthur’s disdain for his elders. He seems to resent his father for sitting around watching television all day, with a snarky comment about how one of his colleagues lost an eye staring at television all day, as well as a long drawn out shot showing a stern facial expression. In the next sequence, Arthur wants to embarrass a sailor for his alcoholism, a method in which many war veterans used to cope with P.T.S.D. Next, after ordering his final pint, Arthur accidentally spills it on an older man, and with a close-up shot we’re made aware he has no intention of apologising. He then purposefully spills the pint on a woman telling him to apologise, before walking off and showing he doesn’t care.

The iconography within the first fifteen minutes is standard for a British new wave film, and a kitchen sink drama. The interiors of the factory, houses and the pub feel claustrophobic, grimy in a way. The mise-en-scene hides nothing from the audience, and it’s supported by the fact that the film was mostly shot on location in Nottingham. The regional dialect and use of British slang compliments this by making the film feel authentic. These are real places lived in by real people, with dialect different to our own, enhancing the realist themes the film portrays. Styan (2001) describes the contrast from conventional mainstream cinema as: “the well-furnished elegance of the middle-class stage gave place to kitchens and attics, with all its sordid paraphernalia of cooking stoves and ironing boards and beds.” Shooting on location became commonplace after the second World War, with many productions wanting to appear as real as possible. This contrasts the traditional Hollywood style of film-making audiences were used to, which featured various sets specifically built for a production.

The film provides a good verisimilitude of what society would have been like during a post-war. Higson (1997) claims that “’kitchen sink’ films are less about the conditions of the industrial working class and their collective class consciousness, than they are about the attempts of individuals to escape from those conditions and that consciousness”, this can be seen evidently within Arthur and Brenda – the woman who he is having an affair with. Arthur wants to be his own individual, free of responsibility but is constantly reminded of societal expectations of men during this period. To cope with his lack of freedom and expression, he gets blackout drunk, injures himself and sleeps around.

On the other hand, Brenda represents women becoming more independent in a post-war Britain. While she does perform a patriarchal role of preparing Arthur’s breakfast the morning after the pair have sex, she goes against the traditional nuclear family role by cheating on her husband – Jack. Jack fulfills the stereotypical male breadwinner role of this time period. He is Arthur’s colleague and is represented as a loving father, but in Arthur’s opening monologue, he is described as someone who has been ‘grinded down’ by his oppressors, and essentially views him as a conformist.

The British New Wave is very distinctive in four elements, its characters, themes, language and setting. It’s a significant turning point in British cinematic history, with its influence still being seen today. The movement changed the direction of cinema from the elegant middle-class productions, to a more real and bold direction within the working-class.

Leave a comment